“It bugs me when people try to analyze Jazz as an intellectual theorem. It’s not. It’s feeling.“

Bill Evans.

Hello, young Padawan

Following in the footsteps of the great Miles and the gigantic John, today we will focus on the intrepid Bill—Bill Evans, of course—another sacred jazz monster.

So, in my eagerness to talk to you about jazz, I’ve made a mistake by starting my articles with Coltrane and Davis, when Bill is the easiest, most natural, and gentle way to get started. But you know, passion, enthusiasm, and the desire to share made me introduce you to his two colleagues first. Well, no one seems to have been traumatized by it; I’ve even received cute messages on Instagram expressing the joy of these respective musical discoveries.

Because yes, jazz is like classical or metal. You don’t play Rachmaninoff or Slayer without first training your ear, otherwise you’ll say “it’s crap,” just as we often reject what we don’t understand, and we miss out on beautiful pieces, certainly, but sometimes also on what could have later become a passion.

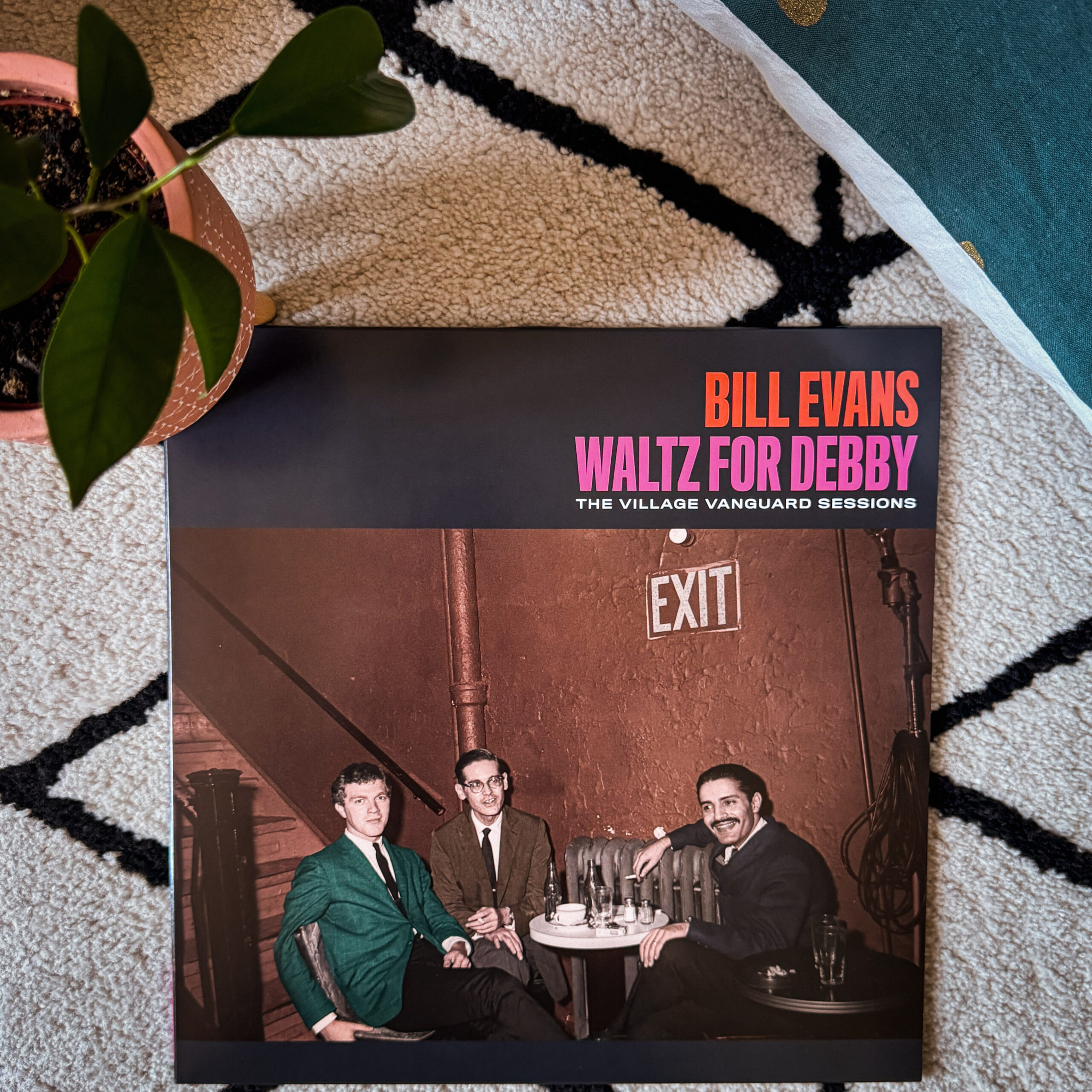

So, let’s discover a legendary Bill Evans theme, even if he had many others: Waltz for Debby.

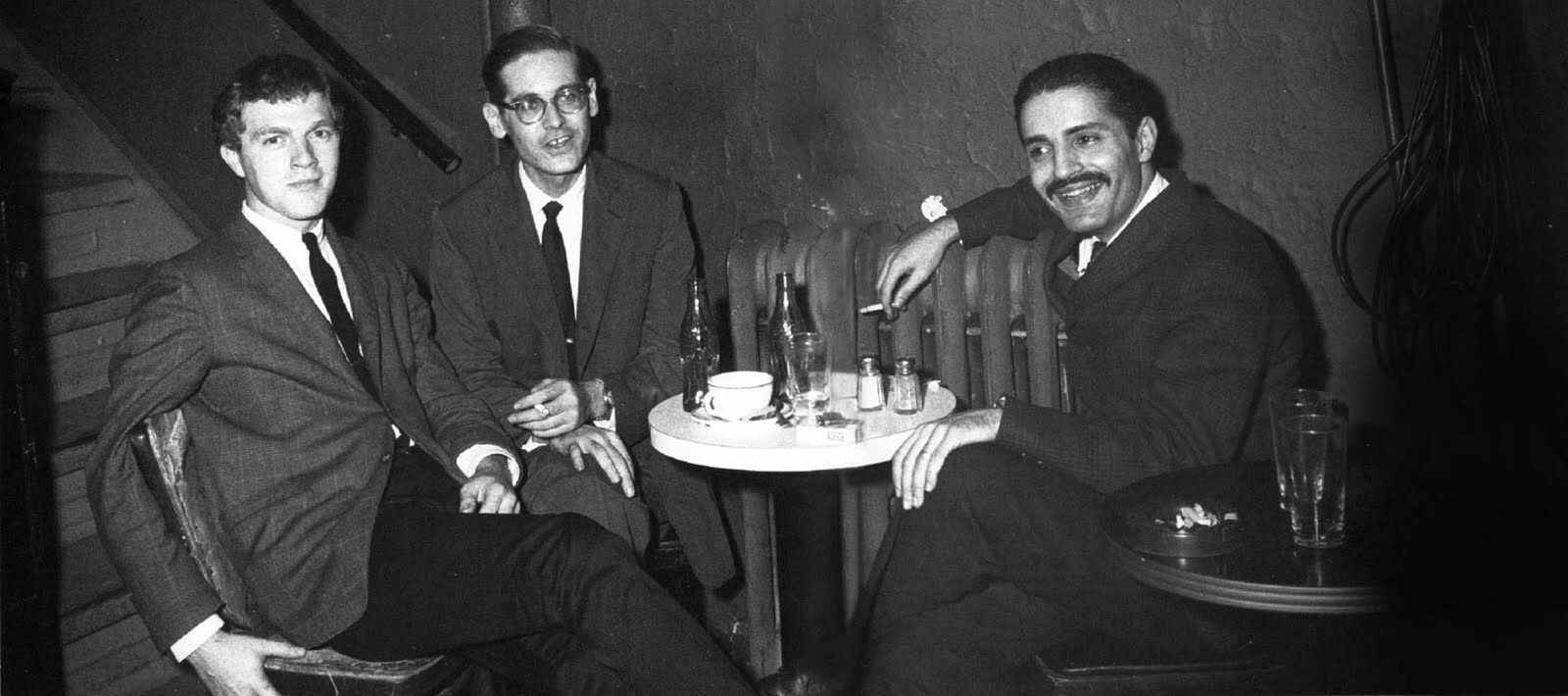

Photo credit: Jazz Recordings – blogspot.

Bill Evans

Born on August 16, 1929, in New Jersey, he grew up in a music-loving family, along with his older brother, who studied piano. At the age of six, he began playing the piano, then the violin (which he would stop playing two years later), and then the flute, sight-reading the classical music scores of 20th-century artists available at home, such as Debussy, Stravinsky, and Milhaud.

He became interested in jazz as a teenager, particularly Bud Powell, Nat King Cole, George Shearing, Horace Silver, and Lennie Tristano, and played in local amateur orchestras.

After three years of military service as a flutist stationed at Fort Sheridan, he began performing and recording with minor New York orchestras while taking composition classes at the Mannes School of Music.

The general public discovered Evans when trumpeter Miles Davis hired him, between February and November 1958, to play in the rhythm section of his sextet with John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley. Inspired by Guinean music, Davis became interested in modal music, and the pianist seemed the ideal partner. But like Adderley and Coltrane, Evans quickly wanted to play in his own groups.

In 1959, he formed a regular trio with double bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian. The three partners, breaking with the tradition of confining the double bassist and drummer to a supporting role, engaged in a true “three-way improvisation.” It is this “interplay”—this constant synergy between the three musicians—that makes this trio so distinctive and modern.

The three partners recorded four albums: Portrait in Jazz (1959), Explorations (1961), and, most importantly, two legendary albums from a single session at the Village Vanguard in New York: Waltz for Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard (June 25, 1961). Scott LaFaro died in a car accident just ten days after recording these albums.

Deeply affected by LaFaro’s death, Bill Evans, although he continued his career as a sideman (accompanying albums for Mark Murphy, Herbie Mann, Tadd Dameron, Benny Golson, etc.), did not record anything as a trio for almost a year.

Nearly 20 years of a prolific career followed, with albums as fantastic as Waltz for Debby. He died on September 15, 1980.

While he was never part of the avant-garde, Bill Evans profoundly revolutionized the approach to jazz trios and piano. He was able to incorporate into his style a particular harmonic color derived from his classical influences (the French Impressionists: Fauré, Debussy, and Ravel, but also Chopin, Scriabin, etc.). His art of voicing (choosing notes for chords) always focused on the upper-midrange of the keyboard to free up space for his double bassist’s bass playing, his sense of rhythmic subtleties (accentuations, polyrhythms, displacement, etc.) and melody, combined with extreme sensitivity, make him one of the major pianists in the history of jazz.

His repertoire consisted mainly of songs from Broadway and Tin Pan Alley, including many waltzes, which he tirelessly covered, but he was also an inspired composer. Many of his compositions have become jazz standards: Waltz for Debby, Very early, Turn out the stars, Time remembered…

Photo credit: Pinterest.

Waltz for Debby

It’s a waltz in F major composed in homage to his niece Debby (daughter of his brother, pianist Harry Evans). The first recorded version can be found on the album New Jazz Conceptions (1956), and he played this theme throughout his career.

This theme is now a jazz standard covered by many musicians. Sometimes, the triple time signature is maintained throughout the piece. Sometimes, the theme is repeated in quadruple time.

Waltz for Debby is a marvel. This music transports you, brings joy to your little heart with a touch of playfulness. In short, it has it all; all you have to do is let yourself be carried away. I’ve put on the version recorded at the Village Vanguard, with LaFaro and Motian, which are my favorite.

As I’ve said in other articles about technical music: if you’re a beginner and at some point get lost in the music, tune your ear to the drums; they will guide you back to the rhythm and understanding of the theme.

So, I hope I’ve been able to introduce some of you to this sublime melody, to give others a chance to listen again, and that all of you had a pleasant time in my company, and especially in that of Bill Evans.

XO 🎵

Sources : Wikipedia, Dragon Jazz, encyclopédie du jazz (ed. Aimery Somogy).